Well, cheerio 2025, it was nice knowing you, but it’s time to move on to 2026 – I must admit, I’m both glad and sad to see it go.

2025 was the year I took time off from writing books (writing two at the same time in 2024-5 required some time away). This doesn’t mean that I took a year off writing: I wrote several pieces for BBC Countryfile Magazine, including one about Plough Monday and Plough Pudding which will appear in the January 2026 edition of the magazine. There was the County Foods series for Country Life too, of course.

I worked with the Museum of Royal Worcester on another project about historic ices and the ways in which they were prepared and served. The previous project ‘Dr Wall’s Dinner’ won the Food on Display award at the inaugural British Library Food Season Awards 2025. I will be teaming up with Paul Crane (who you might remember appeared on the podcast in 2025) to give a talk about the history of sugar and the effect sugar production had on the porcelain manufactory at Worcester porcelain. This talk takes place online in March and will be free to attend. Keep a lookout on the Events page – I’ll update it when I know more details.

I made my first live television appearance in November on Sky News to talk about the history of mince pies – very scary, but I must admit, I did enjoy it!

I also contributed to the Channel 5 series Royal Births, Marriages and Deaths talking about the death of Henry I and his surfeit of lampreys – the episode will be shown in January or February 2026, so keep a lookout for it.

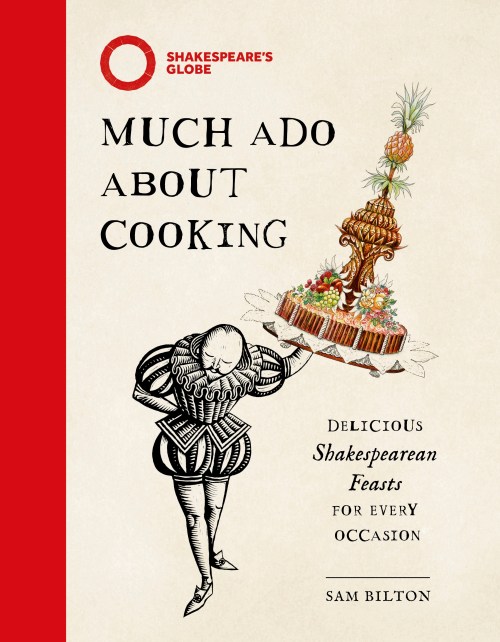

The podcasts have continued to go from strength to strength, and I really pushed hard in this last season (the ninth) of The British Food History Podcast to produce a really varied set of topics. Looking back on the data, the three most popular episodes were: Bronze Age Food & Foodways with Chris Wakefield & Rachel Ballantyne, Special Postbag Edition #6 and Shakespearean Food & Drink with Sam Bilton.

This year also saw the launch of the secret podcast for monthly subscribers.

If you like the blogs and podcast I produce, please consider treating me to a virtual coffee or pint, or even a £3 monthly subscription, where you will receive access to the secret podcast, a monthly newsletter and other premium content: follow this link for more information.

There was ‘Season B’ of A is for Apple: An Encyclopaedia of Food & Drink, too of course, which I co-host with Sam Bilton and Alessandra Pino, which is really gaining popularity now, so if you haven’t checked it out before, please do.

Perhaps the most exciting thing to happen this year was the very first Serve it Forth Food History Festival in October. It was an online event organised by Sam Bilton, Thomas Ntinas, Alessandra Pino and me. It was a fantastic day, and I’m so glad to have seen so many readers of the blog and listeners to the podcasts there. We all organised our own sessions and I was very lucky to have food writer and broadcaster Tom Parker Bowles as a guest. There was also a mini Christmas special looking at the darker side of Christmas and how food plays a role. The four of us are meeting up soon to discuss what will be happening for the next event.

The blog saw lots and lots of puddings this year: early modern black pudding, Gervase Markham’s white pudding, junket, Bakewell tart and a fancy Nesselrode pudding for Christmas. Sticking with frozen desserts, I also went somewhat experimental and made white pudding ice cream and blood ice cream, both of which were delicious!

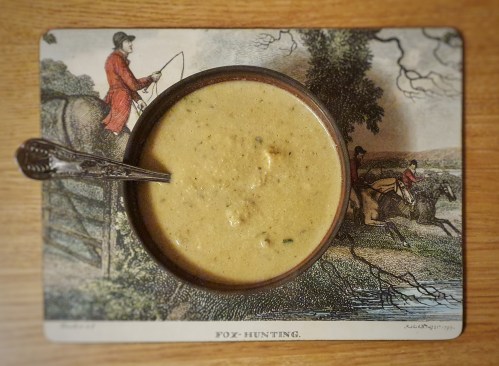

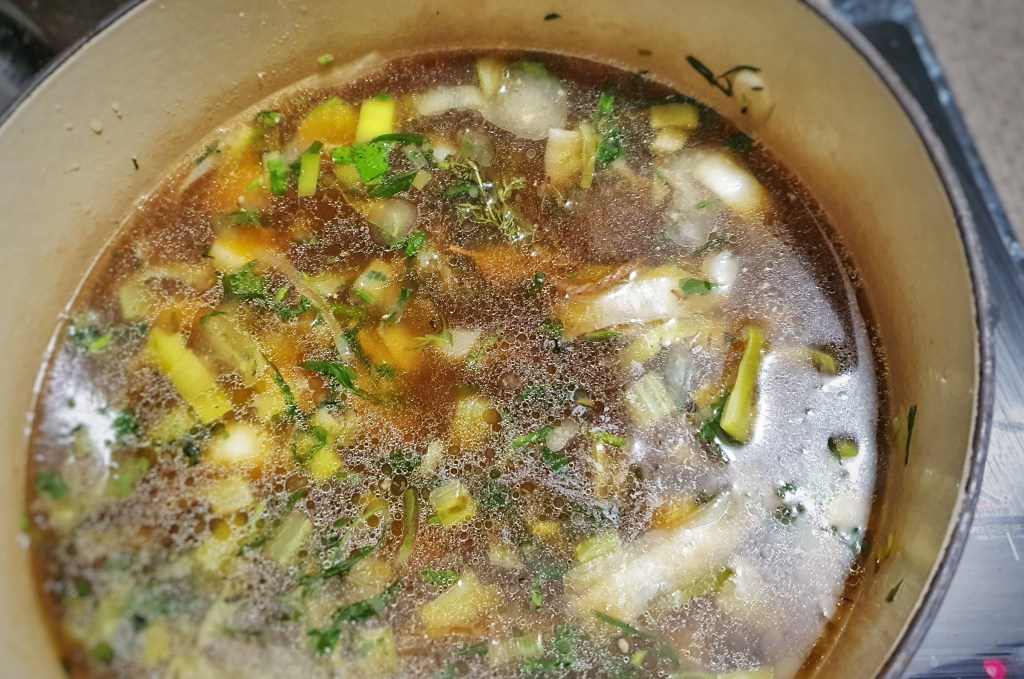

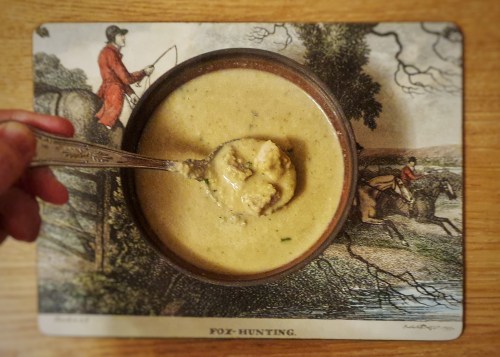

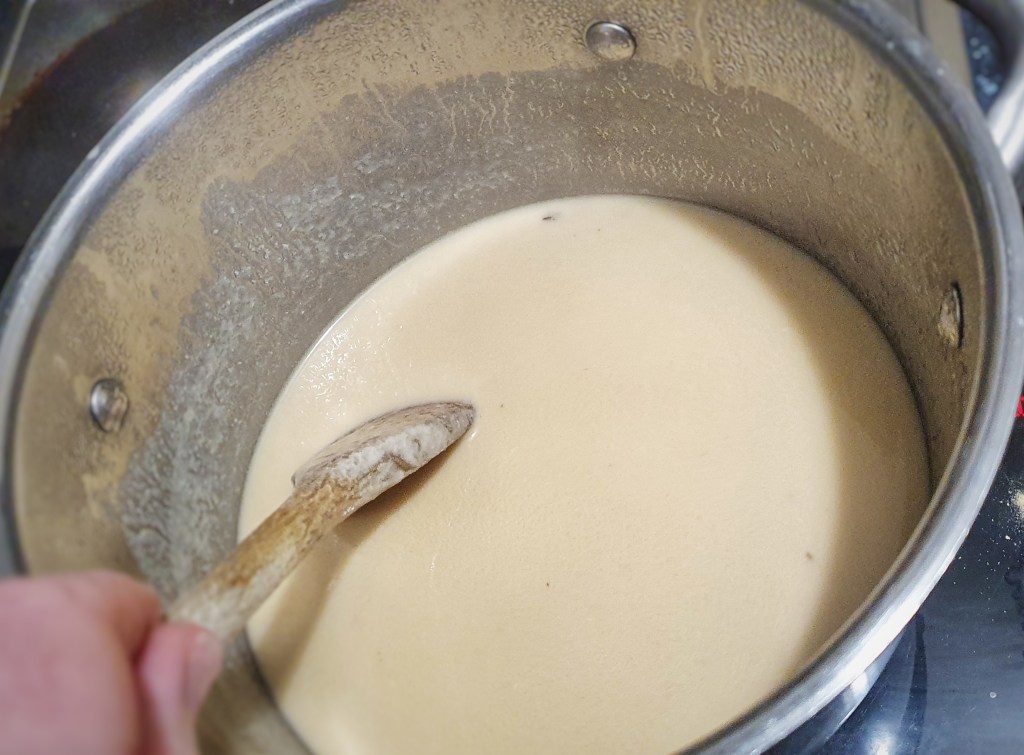

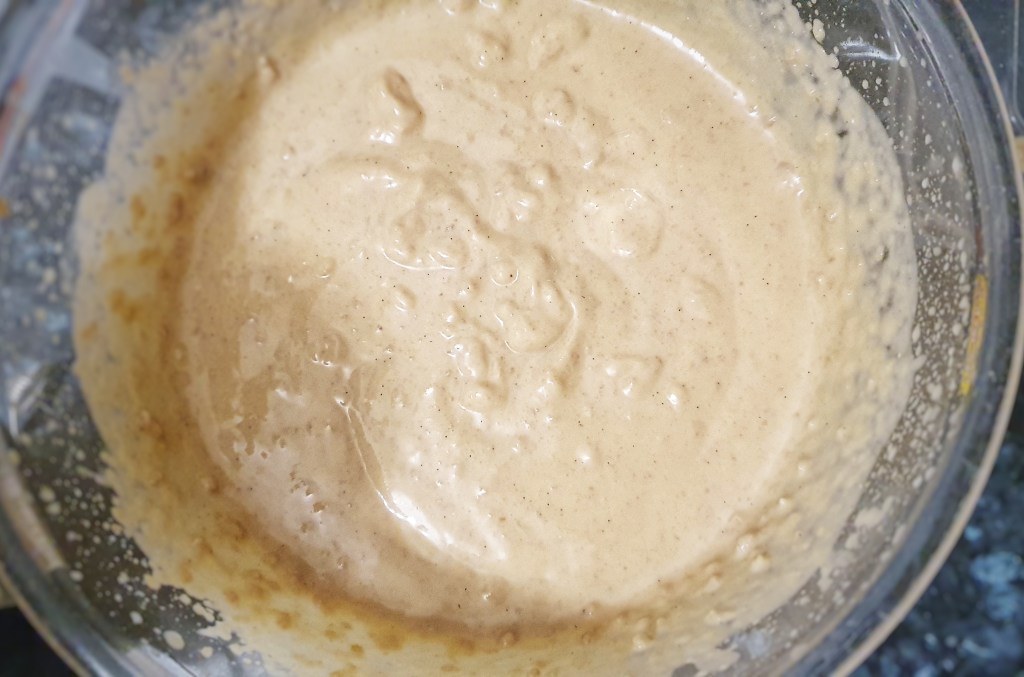

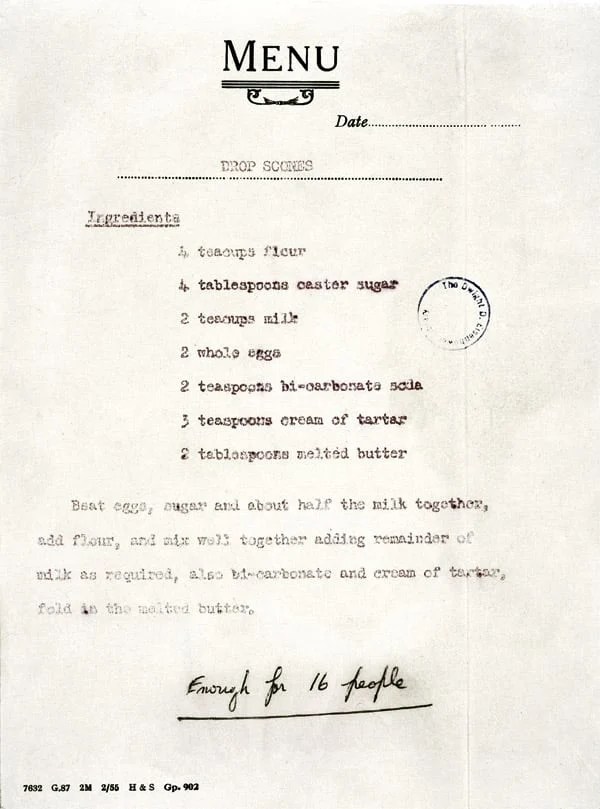

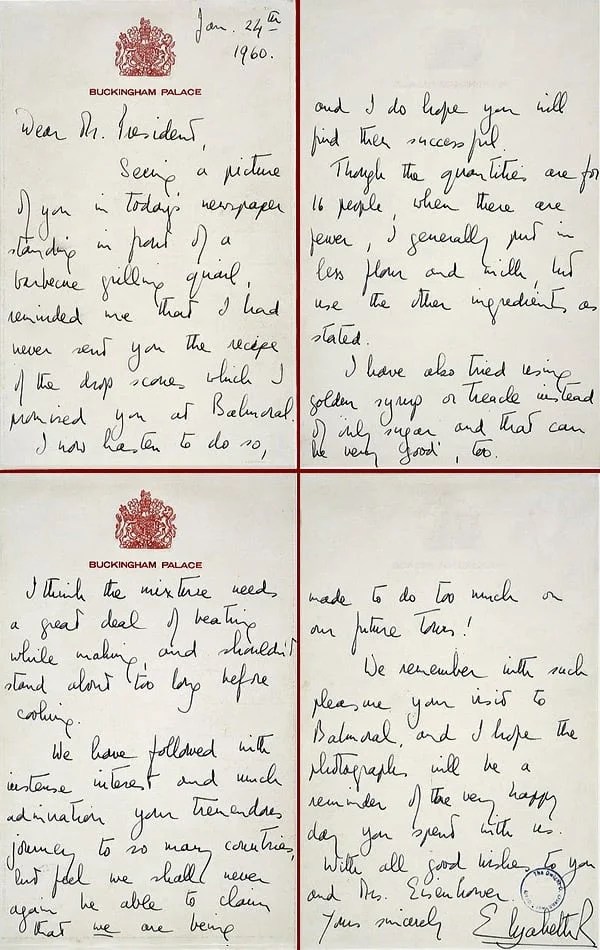

I finally wrote up my recipe for Cumbrian Tatie Pot (informed by the episode of the podcast about black and white pudding). Another recipe I had been meaning to publish for you for ages was one for scones (not one in fact, but four) along with a post about their history. Other recipes included saffron buns, Yorkshire teacakes, lambswool and turkey & hazelnut soup.

Of course, I would be doing none of these things if it wasn’t for all of you fantastic people who read, cook, listen, watch and interact with me, so thank you all for your support, it really does mean a lot.

What about the coming year? Well I have already organised interviews for season 10 of The British Food History Podcast, A is for Apple will certainly be returning, and I will be beginning a brand new book in 2026 – I shall tell you about it as things develop.

Have a great 2026!

Neil x